Hi friends,

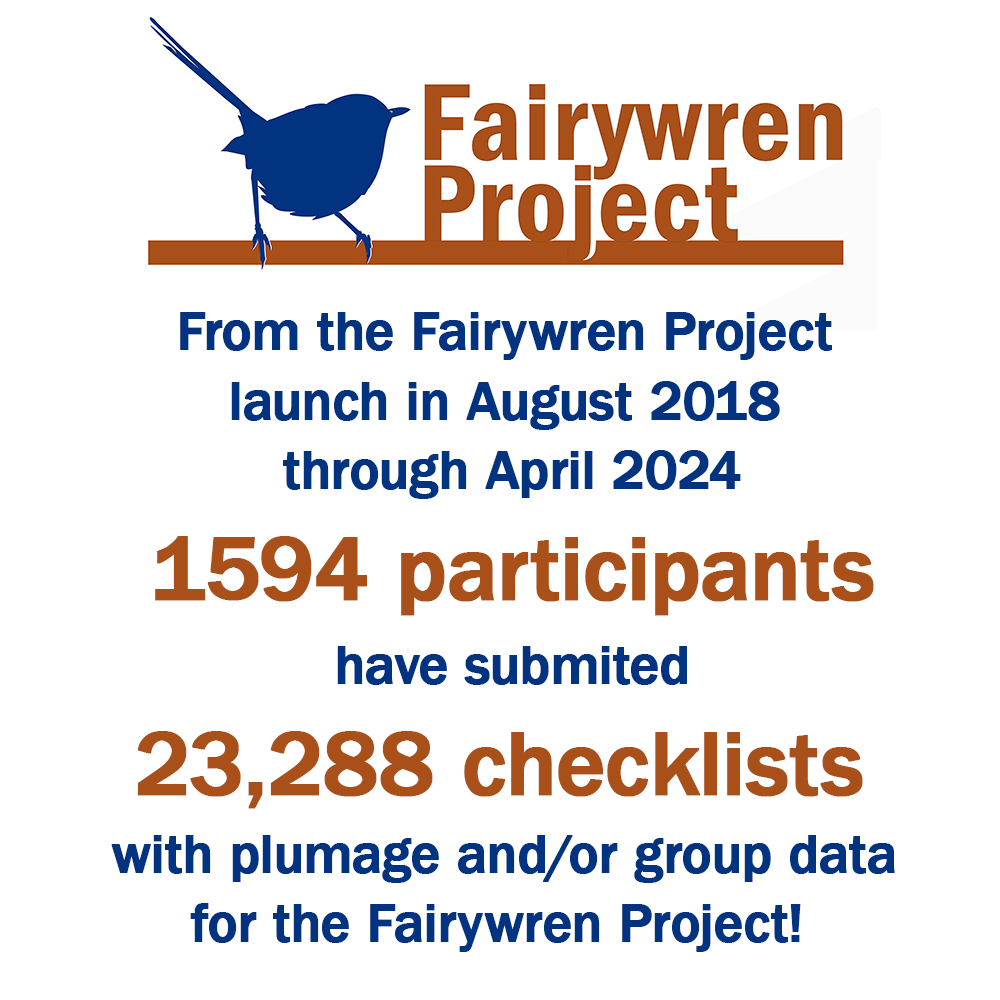

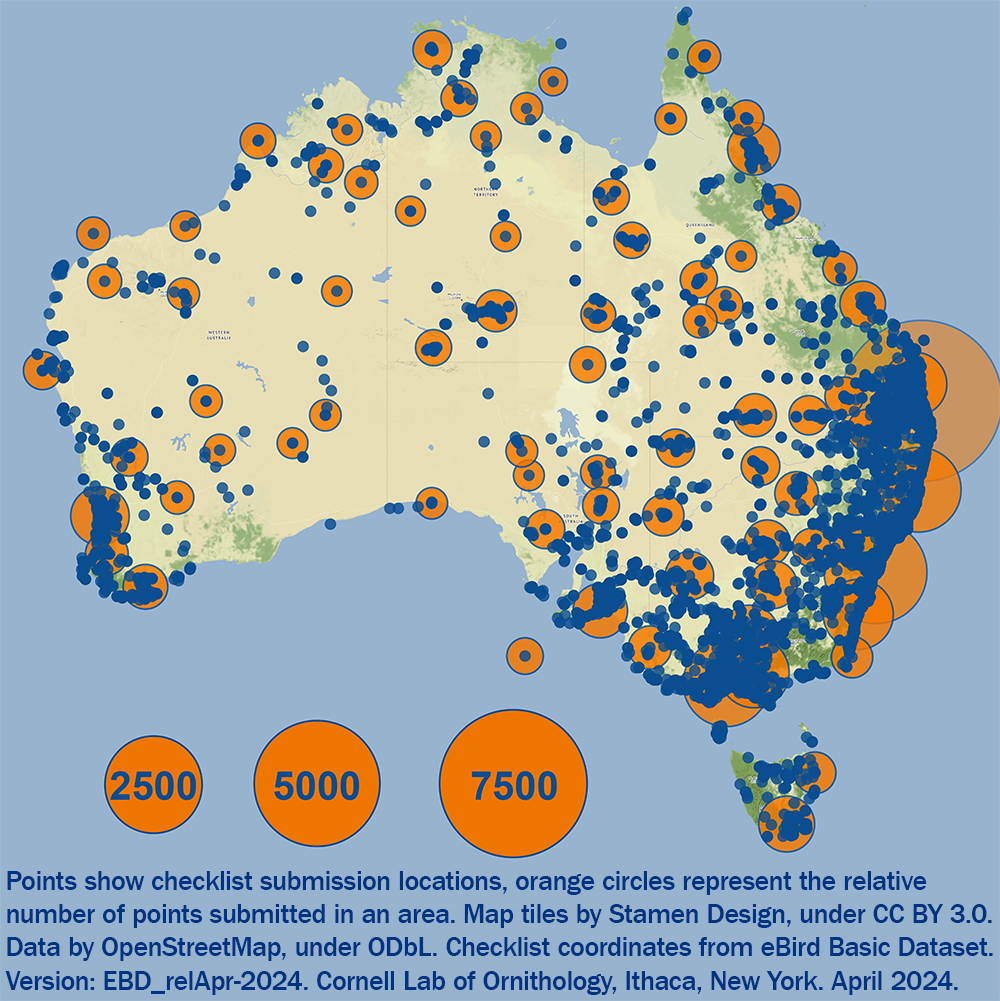

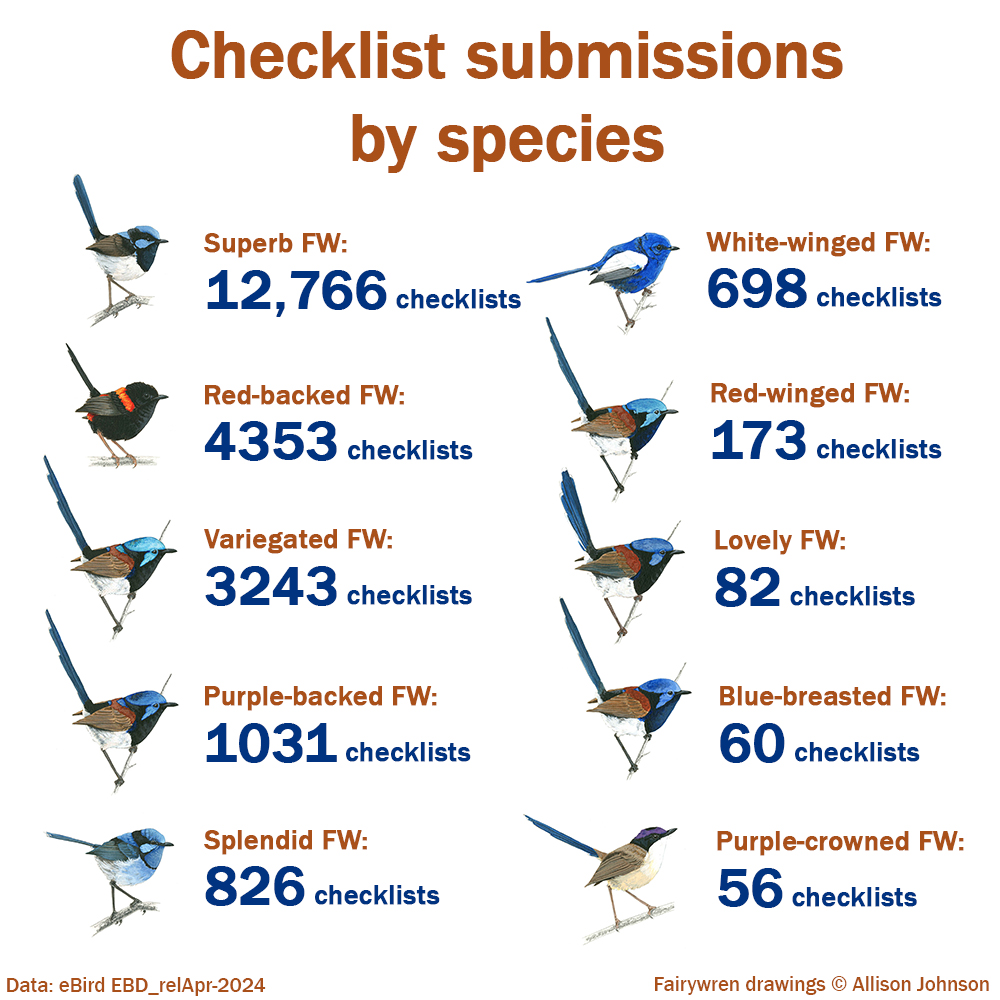

We’re back with another research update! Scroll down for the latest project numbers, but first we’re highlighting some recent fairywren research that we were not involved in, but that we’re really excited about.

The evolutionary history of White-winged Fairywrens

Have you seen a White-winged Fairywren? They’re one of our favorite fairywrens, maybe because they often take a bit of work to find but are always worth the effort. If you live on the west coast, you might see them often, but if you live out east, you’ll likely have to go for a bit of a drive to reach their habitat.

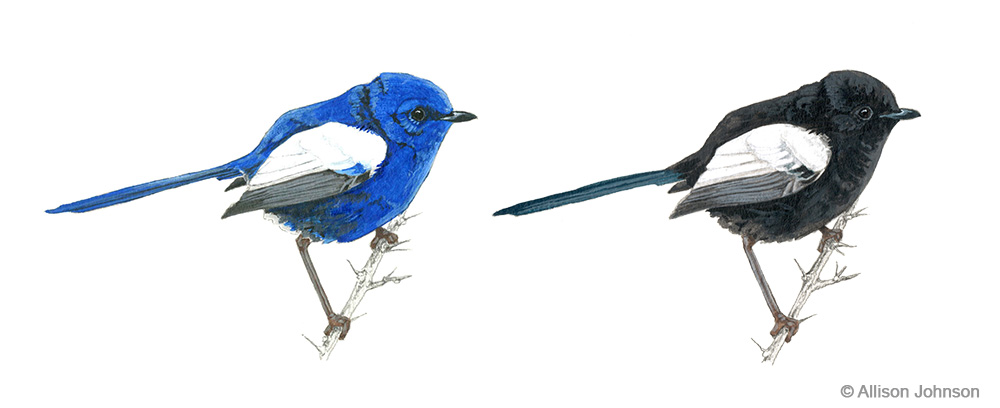

You’re likely familiar with the blue-and-white males of mainland Australia, but did you know there are three White-winged Fairywren subspecies? The blue-and-white subspecies you might have seen ranges over most of Australia, but off the west coast you’ll find Dirk Hartog Island and Barrow Island that have black-and-white males.

Left – drawing of a bright male of the mainland blue-and-white subspecies (Malurus leucopterus leuconotus). Right – drawing of a bright male representative of the two black-and-white subspecies, Malurus leucopterus leucopterus on Dirk Hartog Island, and Malurus leucopterus edouardi on Barrow island.

The big question for fairywren researchers has always been: which came first? Did the black-and-white plumage evolve from the blue-and-white plumage? Or did the blue-and-white plumage evolve from the black-and-white plumage?

Answering this question has become much more approachable with modern genomic techniques. Researchers can now sequence an individual bird’s entire genome from a small blood sample. If you sequence the genomes of multiple individuals from different subspecies, then you can start to understand which subspecies evolved first. A recent scientific paper does this for the White-winged Fairywrens.

Simon Sin and colleagues (including a few Fairywren Project collaborators) first confirmed what previous research had already shown – that the two black-and-white populations on the separate islands are separate subspecies, and that the black-and-white subspecies evolved separately and are not each other’s closest relatives. From here, there are two options.

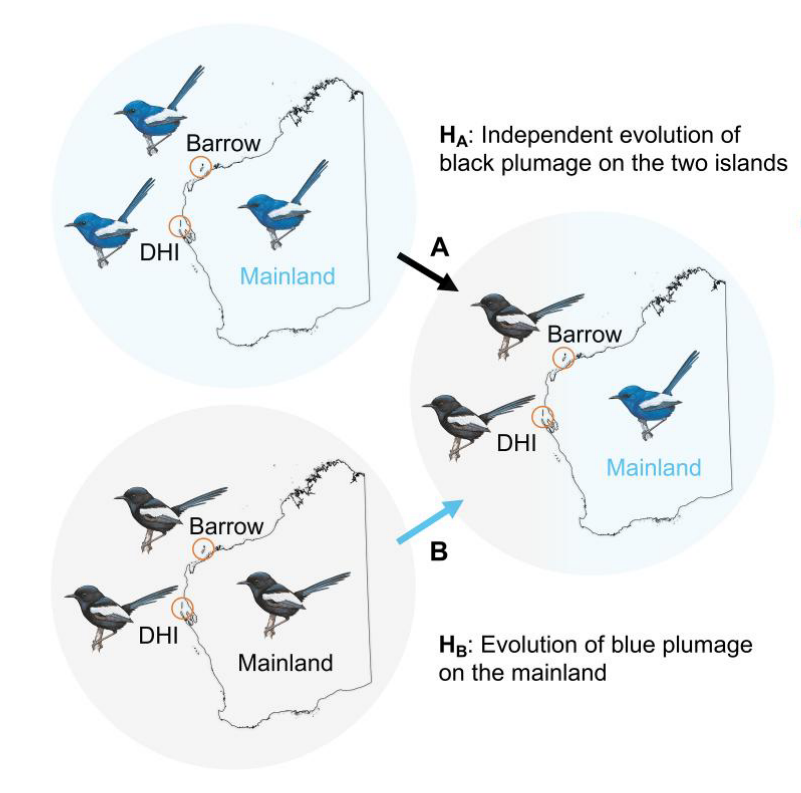

Hypothesis A: the blue-and-white mainland subspecies independently colonized the two islands, and black plumage evolved separately on each island. This independent evolution of the same or similar trait is called convergent evolution.

Hypothesis B: the blue-and-white mainland subspecies was once black-and-white. Then after colonizing each island, the mainland subspecies evolved the blue-and-white plumage. The figure below from the paper shows these two hypotheses:

Figure 2A from Sin et al., 2024.

To test between these hypotheses, Sin and colleagues first compared the genomes of black-and-white and blue-and-white individuals and found many genes that differed between the plumage types. Some of these genes had known functions identified in previous research, and one of them in particular stood out. Agouti signaling protein (ASIP) is associated with the distribution of melanin (brown and black pigments) in the body and the DNA sequences coding this gene showed major differences between the blue-and-white and black-and-white subspecies. Bingo!

Variation in this melanin-producing gene likely explains some of the plumage differences between the subspecies, but which plumage type came first? Next, the researchers looked for what are known as ‘selective sweeps’ in the DNA of the genes that differed between the subspecies. Selective sweep refers to the process by which new beneficial mutations become fixed in a population, and in doing so, sweep, or bring along the genes around them in the DNA sequence.

For example, imagine a random mutation in the DNA coding the ASIP gene leads a normally black-and-white fairywren to produce blue plumage. If females prefer to mate with the blue-and-white male rather than the black-and-white males, the blue-and-white male will produce more offspring than the average black-and-white male and the blue-and-white male’s offspring will likely carry the blue-and-white version of the gene. The sweep part occurs when recombination – the shuffling of genes between chromosomes when sperm and eggs are formed – is decreased in the region of the newly beneficial gene. If recombination results in a reversion of the ASIP gene to the black-and-white form, the resulting male offspring will sire fewer offspring because females prefer the blue-and-white males. This selection against recombination in one gene often results in nearby genes coming along for the ride – being swept up. Thus, a grouping of unshuffled genes around a gene of interest, like ASIP, indicates a recent beneficial mutation.

When Sin and colleagues looked for selective sweeps around the ASIP gene in the black-and-white and blue-and-white subspecies, they actually found it in the mainland blue-and-white subspecies. Since selective sweeps indicate a recent beneficial mutation, this finding indicates that the mainland blue-and-white subspecies evolved more recently, showing support for hypothesis B! Sin et al. conclude that the mainland White-winged Fairywrens were once black-and-white, but they have since evolved the blue-and-white plumage due to females preferring the blue-and-white males.

So next time you see a blue-and-white, White-winged Fairywren, imagine it as black and white, then remember how lucky we are to have both forms!

You can read the scientific paper for yourself here: https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/41/3/msae046/7615515

Sin, S. Y. W., Ke, F., Chen, G., Huang, P. Y., Enbody, E. D., Karubian, J., ... & Edwards, S. V. (2024). Genetic basis and evolution of structural color polymorphism in an Australian songbird. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 41(3), msae046.

Want more info on the genomics parts of this story? Wikipedia has a great figure of how selective sweeps work:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selective_sweep#/media/File:HardSelectiveSweep.jpg

And the University of Utah has a great primer on genetic recombination:

https://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/pigeons/geneticlinkage/

Until next time,

Joe and Allison