Hi all,

We're a bit late in posting this. If you want these early, join our email list!

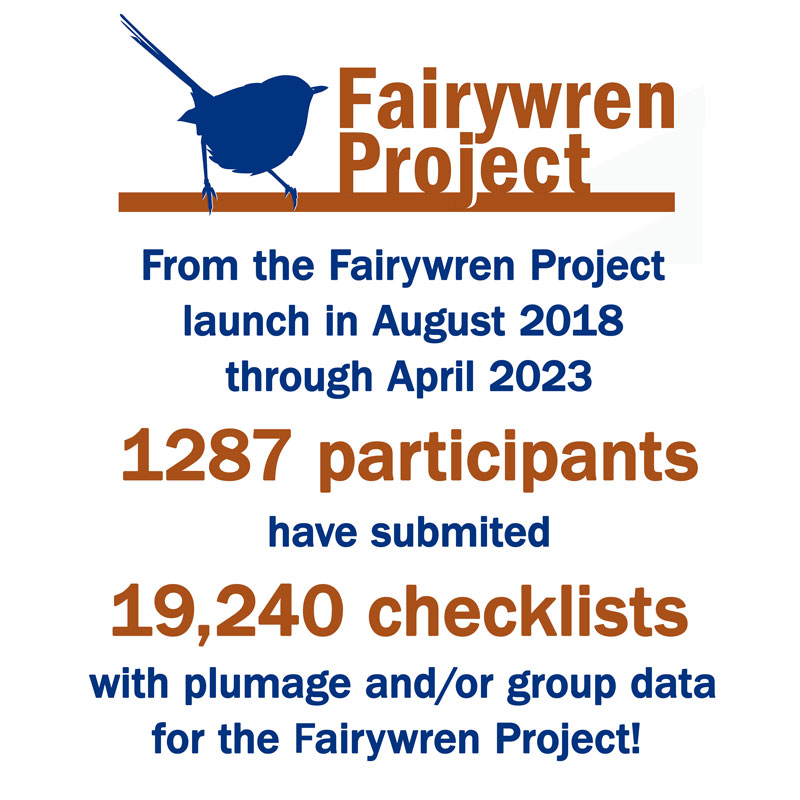

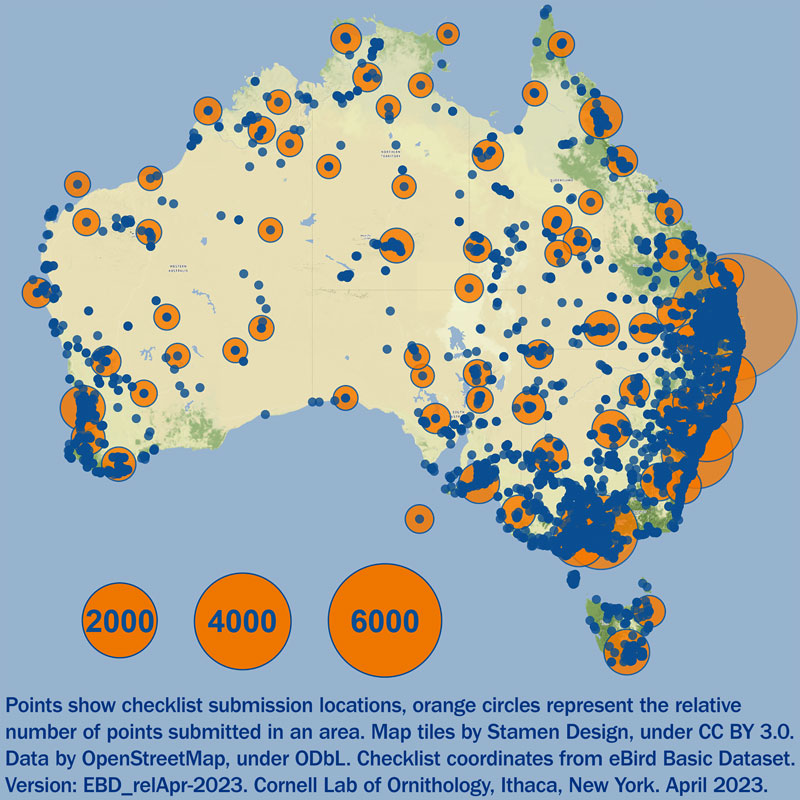

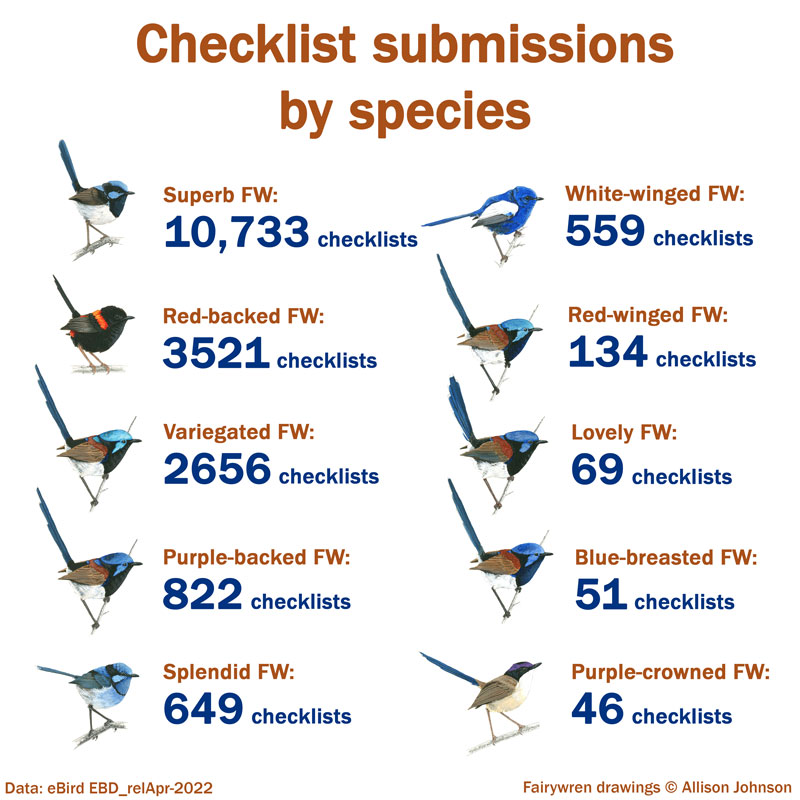

New numbers are in and we have a new paper published! On the numbers front we’re getting close to over 20,000 eBird checklists with plumage and/or group data. We just presented some analyses on these data at the annual American Ornithological Society conference earlier in August and we’ll update you with those results in our next update coming in October. In the meantime, here’s a rundown of our new paper:

Ecogeography of group size suggests differences in drivers of sociality among cooperatively breeding fairywrens

Photo by Sandra Gallienne via eBird (https://macaulaylibrary.org/

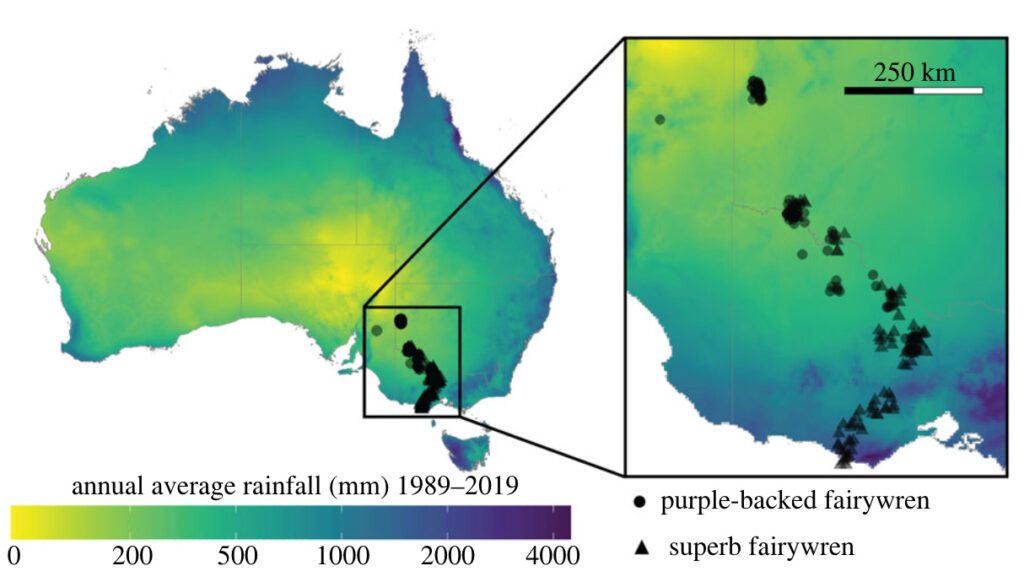

Back in 2018 when Allison and I started the Fairywren Project, we decided it would be useful to supplement the continent-wide data you’re submitting through eBird with a few focused transects across an environment gradient. That led to two trips where we traveled from wet, coastal Victoria, north to dry, arid Broken Hill in New South Wales. Along the way we recorded data on group sizes and plumage types.

Average annual rainfall in Australia from 1989 to 2019. Points represent locations where social groups were observed. Circles are purple-backed fairywren populations and triangles are superb fairywren populations.

Our initial targets during the first transect in 2018 were Purple-backed Fairywrens and White-winged Fairywrens. But as we started, we ran into many Superb Fairywrens, and the White-wings turned out to be much harder to track down than we expected. They are one of our favorite species but we’re constantly amazed and often frustrated by the way a group of White-winged Fairywrens can disappear into the underbrush then reappear 50 meters away in what feels like seconds. Tracking them consistently was going to require more time than we had available.

Above: often the typical viewing distance for White-winged Fairywrens. Below: A bright male Purple-backed Fairywren who was more interested in foraging than in me and my camera.

But both Superb Fairywrens and Purple-backed Fairywrens typically let us get very close for detailed observations of plumages and group sizes. When we came back for the second transect in 2019, we focused entirely on these species. What we found was really interesting!

But first some background: Both species are cooperative breeders, meaning breeding male and female pairs are often joined by additional individuals (helpers) that assist the pair in nest defense and raising offspring. In Purple-backed Fairywrens, breeding pairs with helpers raise more offspring than pairs without helpers, suggesting helpers contribute to nesting success. But in Superb Fairywrens, helpers do not appear to influence nesting success and helping behavior appears to be driven by a lack of suitable breeding territories for young males to disperse into. When a breeding territory does open up, these helper males immediately disperse and the breeding pair can usually raise offspring just fine on their own.

Species that gain reproductive benefits from cooperative breeding, like Purple-backed Fairywrens, tend to occur in harsh, arid environments, likely due to the benefits that cooperative breeding confers when food is limited. Nestling songbirds like fairywrens are dependent on their parents to bring them food, so the more individuals feeding offspring, the more food those offspring are going to receive, and the more likely they will survive.

On the other hand, species that are primarily cooperative due to a saturation of breeding territories, like Superb Fairywrens, tend to occur in mild, wet environments. These productive environments likely have much more abundant and predictable insect prey than harsh, arid environments like the Outback, meaning helpers are not typically needed to raise offspring.

Left: Allison in Greater Bendigo National Park, Victoria. Right: Allison outside of Broken Hill.

But we know little about how species respond to environmental variation across their range. Is cooperative breeding behavior fixed within each species? Or does this behavior change in response to environmental conditions? Both Purple-backed and Superb Fairywrens experience substantial environmental variation across their ranges, with Purple-backed Fairywrens ranging over nearly all of Australia and Superb Fairywrens ranging from the eastern and south-eastern coasts all the way up to the edge of the Outback.

Our question was:

How do different environments influence cooperative breeding behavior in Purple-backed and Superb Fairywrens, and do these species respond to environmental variation in the same way?

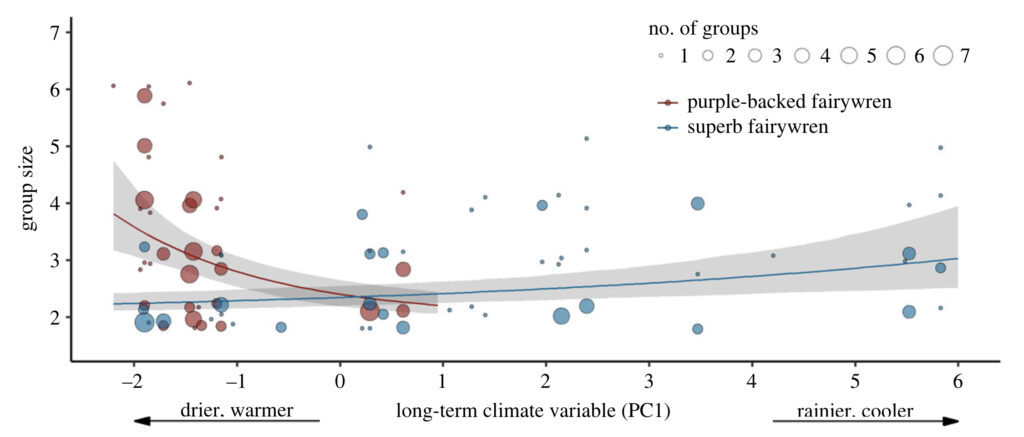

We found that both species exhibited variation in group size across our environmental gradient, but they responded to environmental variation in different ways. Purple-backed Fairywrens exhibited small group sizes in wet habitats and large group sizes in dry habitats, whereas Superb Fairywrens showed the opposite trend. See the figure below.

These results show that a species’ cooperative breeding behavior can respond to environmental conditions and shows that how a species responds is likely shaped by the costs and benefits the species gains from cooperative breeding. For Purple-backed Fairywrens, forming large social groups with many helpers in harsh habitats is likely beneficial for nesting success when food is unpredictable. However, when they occur in wet, mild habitats where food may be more abundant, they don’t need as many helpers to raise offspring.

But Superb Fairywrens appear to mainly form large social groups in wet, mild habitats with abundant food. When we found Superb Fairywrens on the edge of the Outback, they were almost always in pairs and were widely distributed, not clumped together like on the coast, implying that young males have plenty of opportunities to disperse in those regions dominated by harsh habitats and possibly lower nesting success.

Despite the group size trend, we found pairs of both species in nearly every habitat we visited. That’s not too surprising because most fairywren helpers are offspring from previous breeding attempts, meaning large groups can only form if a pair first reproduces on their own, resulting in most populations consisting of a mix of group sizes, including many pairs.

These findings are interesting because they show that cooperative behavior can vary quite a bit within a species in response to local environmental conditions. That means that the Superb Fairywren group sizes you see in your in your garden or local park may be quite different from the group sizes that someone else sees at the other end of the species’ range. These adaptations to different environments can help us understand how species like Purple-backed Fairywrens are able to inhabit most of Australia.

We’re currently working to answer these same questions in the data you’ve been sending. For example, do Superb Fairywrens exhibit this same pattern in relation to rainfall across their entire range? Keep submitting data when you can! We will update you with some of our initial findings later this year.

And thank you for all the data you’ve submitted already! We’re creating quite a database that will be extremely valuable to understanding questions like these on a very broad scale.

Joe and Allison

Read the full paper here.