Hi all,

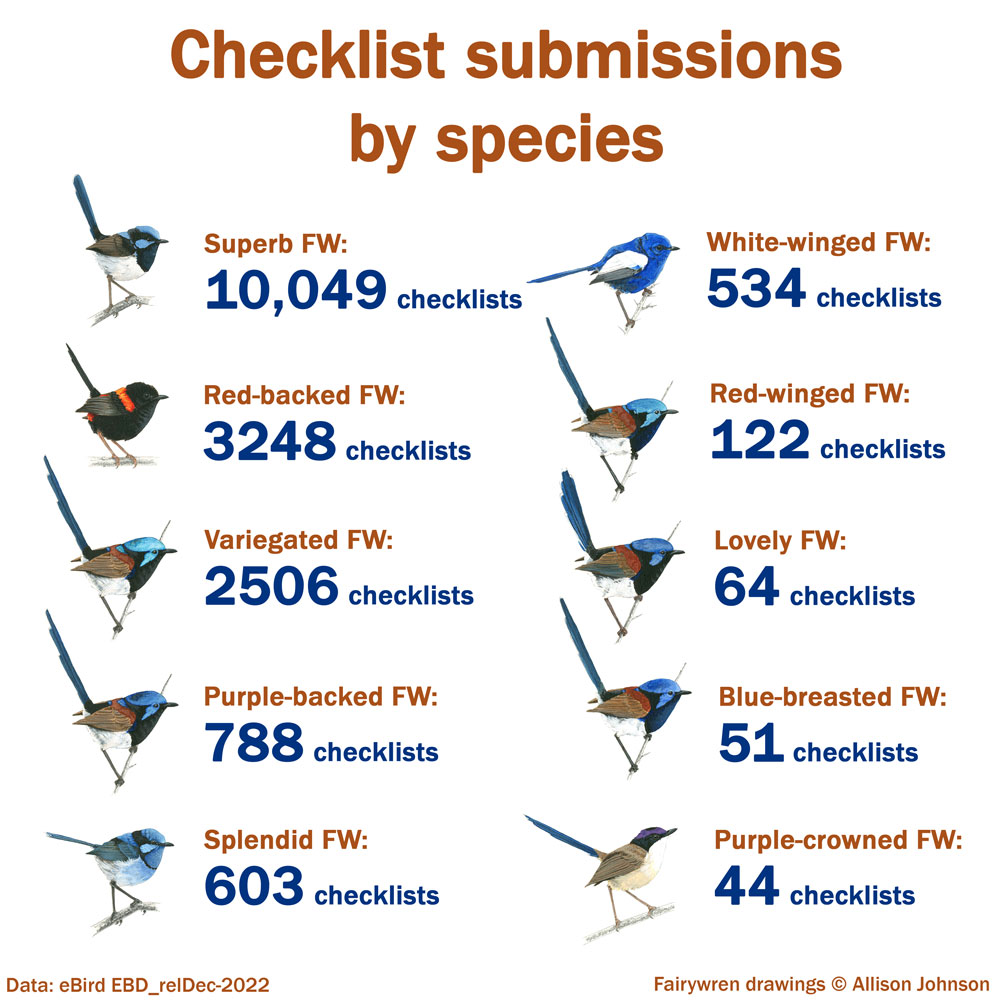

We’re back with another update! We have new numbers for you below and we’re hard at work investigating our first research questions using the data you’ve been submitting. We do not have any results ready to present yet, but in the meantime we thought we would provide a brief overview of a paper on Red-backed Fairywrens that Joe recently published from work completed during his PhD.

Photoperiod and rainfall are associated with seasonal shifts in social structure in a songbird:

You may have noticed in your own observations that the fairywrens near you behave differently in the spring and summer versus fall and winter seasons. Some of the reasons for these differences are obvious – in the spring and summer when fairywrens breed, they need to build nests and defend territories. These breeding territories function as a foraging area where a breeding group can find plenty of food and as a way for males to prevent other males from mating with their female.

However, in the winter, this defending of territories is often not necessary. This is especially true for Red-backed Fairywrens. While they breed primarily in pairs and sometimes have sons that help their parents at the nest, during the winter they can form large foraging flocks. Some previous reports suggest these flock sizes can get over 30 birds!

In this study, we wanted to understand when this transition from a flocking, non-breeding social structure to a territorial breeding social structure occurs, and specifically what environmental variables (such as temperature or rainfall) were associated with when this transition occurs.

My teams and I (Joe) followed groups and flocks of Red-backed Fairywrens during part of the non-breeding season (June-August) in eastern Queensland, just outside of Brisbane for four years. All of the individuals in our population at this time had color bands on their legs (see photo above), allowing us to identify unique individuals during our observations.

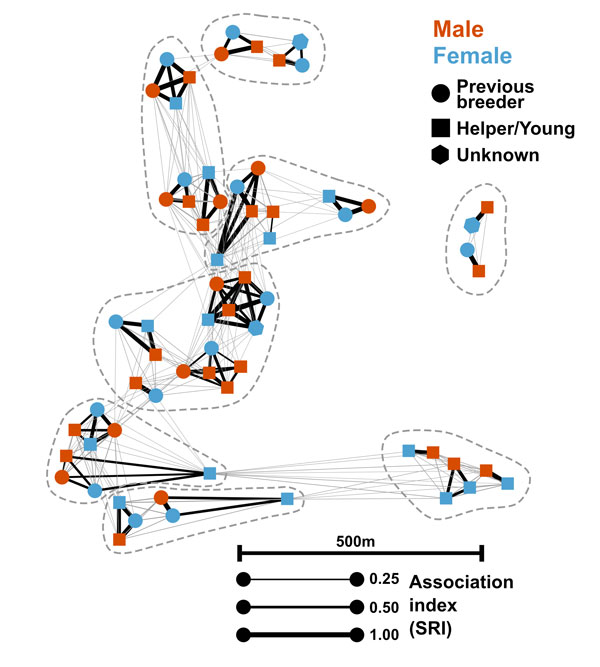

From these observations we were able to create a social network – a visual representation of social relationships:

Each point represents an individual bird that we followed for multiple months and the color and shape of the point conveys information on sex and status. Previous breeders are older birds who bred in the previous breeding season, while helpers and young birds are typically only 6-8 months old, having hatched in the previous breeding season. Lines connecting points show which individuals interacted with one another and thicker lines show individuals that interacted more often with one another than individuals connected by thinner lines.

Immediately by looking at the thickness of the lines you can start to identify specific social groups. Black lines connect individuals in the same social group and gray lines connect individuals in separate social groups. Our observations revealed that Red-backed Fairywrens at our field site almost always traveled in social groups and that these social groups were typically family groups composed of parents and their offspring from the previous breeding season. The dotted gray lines show larger social communities composed of social groups that interacted often.

Here's an example of what a social group can look like. I took this video just after arriving in Australia one year, so some of the birds do not have bands yet. The red-and-black (bright) individual is the male, the brown bird with the single band on each leg is the female and the other two brown birds are their two offspring from the previous breeding season.

So when you see flocks of Red-backed Fairywrens during the non-breeding season or winter, you’re likely seeing multiple social groups forming up together. Similar research from a group at Monash University indicates the same patterns occur in Superb Fairywrens down in Melbourne.

When we compared these interactions among social groups to environmental conditions, we found that rainfall is associated with interaction rates among social groups. Greater rainfall 1.5 - 2 months before an observation was associated with fewer interactions among social groups on that day. This likely means that Red-backed Fairywrens are responding physiologically to the effects of rainfall in the non-breeding season, such as greener vegetation and increased insect abundance, resulting in changes in their social behavior as they become more and more territorial as the breeding season approaches.

If you want to read the full paper you can download it here: LINK

Questions? Contact us! We’re always happy to chat: fairywrenproject@gmail.com

A note on data quality in your eBird observations:

Almost all of you are submitting observations that are easily interpretable and usable, but a few participants appear to be submitting plumage observations using only “male” and “female” codes. Male and female codes alone do not give us much information to work with because males can come in multiple plumage types (LINK). If you can, either use our suggested codes: bright (b), intermediate (i), dull (d), female (f), juvenile (j), or something similar that is easily interpretable for us. For example, if you say “moulting male” we know that’s an intermediate male, if you say “brown male” we know that’s a dull male.

Thanks!

Joe and Allison